![]()

Bach to

Hypnosis

Products Home

Page

Hypnotic

Language

& other Secrets

E-books and Programs for sale

Brainwave

Synchronization

The added Advantage

Brainwaves

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a study of the changing electrical potential of the brain. The aparatus used to measure this electric potential of the brain is called electroencephalograph, and the tracing or the printout of the measured brainwave forms is electroencephalogram.

Frequency is the number of complete repetitive waves that occur in a given unit of time. Frenquency is easured in Hertz (Hz) or cycles per second (cps). According to their frequency brainwaves are devided into 4 main groups, also referred to as "brain states"

EEG Brainwave Sample |

Brainwave |

State of Consiousness |

|

BETA 14 - 40 cps |

Fully Awake and Alert |

|

ALPHA 8 - 13 cps |

Relaxed, Daydreaming Generally associated with right-brain thinking activity - subconscious mind - a key state for "relaxation" |

|

THETA 4 - 7 cps |

Deeply Relaxed, Dreaming Generally associated with right-brain thinking activity - deeper subconscious to superconscious Access to insights, bursts of creative ideas - a key state for "reality creation" through vivid imagery |

|

DELTA 0.5 - 3.5cps |

Dreamless Generally associated with no thinking - unconscious / superconscious Access to non-physical states of existence - a key state for "regeneration" and "rejuvenation" |

Some research has been done associated with the activities and benefits of other brainwave frequencies, such as Super Beta, Gamma, etc.

The lower your brainwave cps, the more your awareness is turned toward your subjective experience, toward your inner world and the more effectively are you able to use the power of your mind to create changes in your body. With each lower state you become more fully aligned with the source of power within you, with your unconscious, or if you prefer, with that part of you that is greater than you (your body).

Generally in while in the Beta state, your attention is focused outward. In alpha it begins to turn inward, and in theta and delta it goes further and further inward. The deeper you go, the more effectively are you able to enter your subconscious.

You can imagine that at the borderline between Beta and Alpha States is a doorway to your subconscious mind, and the doorway consists of what hypnosis refers to as your critical faculty.

You can imagine that at the borderline between Alpha and Theta states is a doorway to your superconscious mind, where you begin to gain access to your "supernatural abilities", which for most people manifest as bursts of insight. The more time you spend in this state, even if you're not intentionally attempting to create a change, the more these "abilities" begin to become part of you - you may firstly notice that the time-lag between what you think and it's manifestation in your outer world becomes shorter and shorter.

And you can imagine that at the borderline that between Theta and Delta, you're beginning to say "good-bye" to your physical experience of the world, as you're getting altogether into experiencing yourself as a non-physical being. Here your body is only a thought in your mind. If you are able to maintain your consciousness at this level, you can effect instant changes in the outer world. In this state, you can transcend the "laws of the physical world" because you're not bound by them any more.

Whenever you think, you expand energy. In the deep, dreamless Delta state, where your mind is fully resting, your body has the best opportunity to regenerate.

With meditative practice and

self hypnosis, you develop the ability to remain conscious while

getting progressively into deeper and deepr states. For example, a person

without any mind training will tend to fall asleep when getting into the

theta state, while a person who has undergone some form of meditative

mind-training will be able to be very deeply relaxed, yet conscious.

The more you are able to remain conscious while in deeper states

of mind, the less sleep you will require.

Brainwave Entrainment and Synchronization

Syncronized Brainwave Patterns Enhanced Ability |

Incoherent Brainwave Patterns Limited Ability |

|

|

MAX

|

|

Brainwave synchronization

techology provides a shortcut to experiencing deeper states of mind giving

you an opporunity to access higher states of consciousness and extraordinary

abilities in a very short time through brainwave entrainment. This way

you can experience almost immediately the effects that took someone years

of meditation to achieve.

And the process is effortless. All you need to do is use your headphones.

Here's how the principle of entrainment works. Entrainment is the process of synchronization, where vibrations of one object will cause the vibrations of another object to oscillate at the same rate. External rhythms have a direct effect on the psychology and physiology of the individual.

You can observe these principles anywhere in nature as ultimately everything is made out of energy that resonates at a specific frequency. If you put several pendulum clocks on the wall and set them to swing at different rates, in time they will get synchronized, all of them swinging in unison. It has been noted thad women sleeping in the same dormitory whose menstral cycles would occur at different times of the month, would in time tend to synchronize their internal clocks to the same mensrtal cycle automatically. People who live together for many years, may even tend to look alike, as their energies are becoming synchronized. Another side effect would be increased telepathic ability between them - they'd just find that they would think the same thought at the same time, and perhaps surprise themselves by saying out loud the same word at the same time. In NLP, this entrainment with another person is often intentionally done through matching a breathing pattern.

The application of the principle of brainwave entrainment to alter states of mind is not new. Drumming and chanting have been used in different cultures to create rhythmic patterns which would stimulate altered states of consciousness .

With technology this process has gone digital through the use of binaural beats. This is accomplished by sending two different sounds (tones) to each ear through stereo headphones. The two hemispheres of the brain then work in unison to "hear" the third signal, which is not played, but rather produced as a result of the difference in frequency between the two beats that are heard. Sending specific frequencies to each ear entrains the brain to enter effortlessly into a specific state of mind.

If

the left ear is presented with a steady tone of 400Hz and the right ear

a steady tone of 407Hz, these two tones combine in the brain. The difference,

7Hz, is perceived by the brain and is a very effective stimulus for brainwave

entrainment. This 7Hz is formed entirely by the brain. When using stereo

headphones, the left and right sounds do not mix together until in your

brain. The frequency difference, when perceived by brain this way, is

called a binaural beat.

All Hypnotic Advancements self

hypnosis recordings are enhanced with brainwave synchronization

to help you enter the appropriate states of mind to further help enable

you to create your desired changes effortlessly.

![]()

Excerpts

from Research on the Influence of Brain Wave Synchronization

On Pain Relief

Originally Published: J Neurol

Orthop Med Surg (1996) 17:32-34, The Journal of Neurological and Orthopaedic

Medicine and Surgery, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1996

Authors: Richard H. Cox,

Ph.D., MD, C. Norman Shealy, MD, Ph.D., Roger K. Cady, MD, Saul Liss,

Ph.D.

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Life Science Foundation.

Although it has been known since

shortly after the development of the EEG that brain wave activity "follows"

repetitive light and sound frequencies', and experiments using brain wave

synchronization (BOOS) as a tool to assist in relaxation and induction

of the focused state of hypnosis were done as early as 1948,

the first brain wave synchronizer (BOOS) was introduced commercially in

1958 by Sidney A. Schneider.

Schneider and coworkers specifically noted that over 90% of approximately

2,500 subjects treated by 1959 had had induced light to deep hypnotic

trance with the use of the BOOS. His instrument consisted of a photic

stimulator, controlled by the therapist or client, with variable frequencies

ranging from low delta (0-1 Hz) to beta frequency (above 13 Hz). Schneider

noted that each individual became entrained at a specific frequency which

led to a "a rainbow effect, fingers tingling, eyelids heavy, complete

relaxation," "a whirlpool effect, anesthesia, or dissociation"

- "The point of least resistance" for that individual to enter

a trance state, assisted by audiotapes or a live hypnotic induction.

The editor of HYPNOSIS QUARTERLY reported rapid induction of a deep trance in a previously unhypnotizable subject using BOOS, to the depth of cataplexy, analgesia and amnesia3.

The JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION in March, 1959, mentioned the "hypnosis machine" which could be used to speed up hypnotic induction and to "help make labor and delivery a more gratifying experience by reducing discomfort and the need for excessive analgesia and anesthesia."4

In June 1966, Bernard S. Margolis, D.D.S.5, reported the BWS was "a valuable tool for allaying fears and apprehensions," and noted that coupled with hypnosis -

1. Patients required less

anesthesia.

2. Some patients could have dental procedures without external anesthetics.

3. No physiologic depression occurred.

4. Healing was more rapid.

5. Gagging could be controlled.

6. The frequency could be controlled by the patient.

Dr. William A. Phillips reported "the reduction and control of high blood pressure of inorganic origin," with reduction of 10 to 40 mm. of Mercury, using only BWS without verbal hypnotic suggestion6. And Sadove emphasized the use of BWS to assist relaxation7.

Comparisons were made between cranial electrical stimulation (The Pain SuppressorO), several different models of light frequency BOOS, the brainwave synchronization tapes, and self hypnosis audiotapes.

Patients were asked to grade their depth of relaxation and intensity of pain before and after 30 minutes of synchronization. Blood pressure and pulse measurements were also done before and after BOOS.

More recently we have also measured blood neurochemicals (NE, MEL, BE, ST, and CHE) before and after brain Shealy RelaxMate indicate: wave synchronization coupled with the self hypnosis audiotape in eight individuals.

With brainwave synchronization tapes alone or self hypnotic tapes alone, depths of relaxation were similar. Relaxation music and cranial electrical stimulation were slightly less effective than BWS (50% to 60% relaxation usually).

When brainwave stimulation

was combined with self hypnosis tapes, consistent relaxation

depths of 70% to 100% were reported.

In 72 patients in whom blood pressure, pulse, and

pain intensity were measured, blood pressure and pulse were reduced 4%

to 10% in 58 patients, and pain was decreased 30% to 100% in 60 patients

(average over 50%). Almost invariably the

combination of brainwave synchronization plus self-hypnosis

was more effective than either alone. The

blood pressure and pulse effects are compatible with the relaxation response.

The degree of pain relief,

however, is greater than that reported with

the relaxation response alone.

In eight individuals, blood neurochemicals have been measured before and after 30 minutes of alpha rhythm (10 Hz) BOOS. Melatonin has been reduced 5% to 20% (average 6% decrease) and beta endorphin has been increased 10% to 50% (average 14% increase). Interestingly, these same individuals have an average increase in serotonin of 23% and an increase of norepinephrine by 18%.

Our experience with BWS coupled with guided mental relaxation exercises (BWS/SH) confirm Schneider's reports that at least 90% of individuals achieve deepened levels of focused relaxation with those techniques. Our results are also compatible with those of Benson and others who indicated that the relaxation response is a major stress reducer and assists the process of homeostasis'°.

The increase in beta endorphins after BWS/SH is associated with a sense of well-being and decreased pain. Even though blood pressure and pulse usually decrease with BWS/SH, the increases in norepinephrine and serotonin and the decrease in melatonin suggest an increased level of alertness. This may well be consistent with Schultz's description of poised alertness reported with autogenic training". Decreases in melatonin, as found, are to be expected with exposure to light and suggest that BSW may be useful for seasonal affective disorders.

It is interesting to speculate that various BWS rates might affect neurochemicals differently. Since most individuals choose the lowest theta rates, those rates might increase beta endorphins more without the increases in norepinephrine and/or serotonin. Further study needs to be done to elucidate potential differences. It has been noted that BWS for greater than 40 minutes often leaves individuals feeling groggy instead of alert immediately after a session. Thus, we recommend 15 minute sessions most of the time. Benson reported that two daily 20 minute deep relaxation sessions led to decreased insulin requirements and catecholamine production for up to 24 hours.

Finally, we have noted that BWS even without self hypnosis leads to enhanced sleep induction, especially at the selfselected low theta rate. And return to sleep is more rapid with BWS if one awakens during the night and uses BWS to return to sleep.

Binaural Beats

Binaural

beats are auditory brainstem responses which originate in the superior

olivary nucleus of each hemisphere. They result from the interaction of

two different auditory impulses, originating in opposite ears, below 1000

Hz and which differ in frequency between one and 30 Hz (Oster, 1973).

For example, if a pure tone of 400 Hz is presented to the right ear and

a pure tone of 410 Hz is presented simultaneously to the left ear, an

amplitude modulated standing wave of 10 Hz, the difference between the

two tones, is experienced as the two wave forms mesh in and out of phase

within the superior olivary nuclei. This binaural beat is not heard in

the ordinary sense of the word (the human range of hearing is from 20-20,000

Hz). It is perceived as an auditory beat and theoretically can be used

to entrain specific neural rhythms through

the frequency-following response (FFR)--the tendency for cortical potentials

to entrain to or resonate at the frequency of an external stimulus. Thus,

it is theoretically possible to utilize a specific binaural-beat frequency

as a consciousness management technique to entrain a specific cortical

rhythm.

Uses of audio with embedded binaural beats that are mixed with music or various pink or background sound are diverse. They range from relaxation, meditation, stress reduction, pain management, improved sleep quality, decrease in sleep requirements, super learning, enhanced creativity and intuition, remote viewing, telepathy, and out-of-body experience and lucid dreaming. Audio embedded with binaural beats is often combined with various meditation techniques, as well as positive affirmations and visualization.

When signals of two different frequencies are presented, one to each ear, the brain detects phase differences between these signals. "Under natural circumstances a detected phase difference would provide directional information. The brain processes this anomalous information differently when these phase differences are heard with stereo headphones or speakers. A perceptual integration of the two signals takes place, producing the sensation of a third "beat" frequency. The difference between the signals waxes and wanes as the two different input frequencies mesh in and out of phase. As a result of these constantly increasing and decreasing differences, an amplitude-modulated standing wave -the binaural beat- is heard. The binaural beat is perceived as a fluctuating rhythm at the frequency of the difference between the two auditory inputs. Evidence suggests that the binaural beats are generated in the brainstem’s superior olivary nucleus, the first site of contralateral integration in the auditory system (Oster, 1973). Studies also suggest that the frequency-following response originates from the inferior colliculus (Smith, Marsh, & Brown, 1975)" (Owens & Atwater, 1995). This activity is conducted to the cortex where it can be recorded by scalp electrodes.

Binaural

beats can easily be heard at the low frequencies (< 30 Hz) that are

characteristic of the EEG spectrum (Oster, 1973). This perceptual phenomenon

of binaural beating and the objective measurement of the frequency-following

response (Hink, Kodera, Yamada, Kaga, & Suzuki, 1980) suggest conditions

which facilitate entrainment of brain waves and altered states of consciousness.

There have been numerous anecdotal reports and a growing number of research efforts reporting changes in consciousness associated with binaural-beats. "The subjective effect of listening to binaural beats may be relaxing or stimulating, depending on the frequency of the binaural-beat stimulation" (Owens & Atwater, 1995).

Binaural beats in the delta (1 to 4 Hz) and theta (4 to 8 Hz) ranges

have been

associated with reports of relaxed, meditative, and creative states

(Hiew, 1995),

and used as an aid to falling asleep. Binaural beats in the alpha frequencies

(8 to 12 Hz) have increased alpha brain waves (Foster, 1990) and binaural

beats in the beta frequencies (typically 16 to 24 Hz) have been associated

with reports of increased concentration or alertness (Monroe, 1985)

and improved memory (Kennerly, 1994).

Passively

listening to binaural beats may not spontaneously propel you into

an altered state of consciousness. One’s subjective experience in

response to

binaural-beat stimulation may also be influenced by a number of mediating

factors. For example, the willingness and ability of the listener to relax

and focus attention may contribute to binaural-beat effectiveness in inducing

state changes. "Ultradian rhythms in the nervous system

are characterized by periodic changes in arousal and states of consciousness

(Rossi, 1986; Shannahoff-Khalsa, 1991; Webb & Dube, 1981). These naturally

occurring shifts may underlie the anecdotal reports of fluctuations in

the effectiveness of binaural beats. External factors are also thought

to play roles in mediating the effects of binaural beats" (Owens

& Atwater, 1995). The perception of a binaural beat is, for example,

said to be heightened by the addition of white noise to the carrier signal

(Oster, 1973), so white noise is often used as background. "Music,

relaxation exercises, guided imagery, and verbal suggestion have all been

used to enhance the state-changing effects of the binaural beat"

(Owens & Atwater, 1995). Other practices such as humming, toning,

breathing exercises, autogenic training, and/or biofeedback can also be

used to interrupt the homeostasis of resistant subjects (Tart, 1975).

Brain Waves and Consciousness

Controversies

concerning the brain, mind, and consciousness have existed

since the early Greek philosophers argued about the nature of the mind-body

relationship, and none of these disputes has been resolved.

Modern

neurologists have located the mind in the brain and have said that consciousness

is the result of electrochemical neurological activity.

There are, however, growing observations to the contrary. There is no

neurophysiological research which conclusively shows that the higher

levels of mind (intuition, insight, creativity, imagination, understanding,

thought, reasoning, intent, decision, knowing, will, spirit, or soul)

are

located in brain tissue (Hunt, 1995).

A

resolution to the controversies surrounding the higher mind and consciousness

and the mind-body problem in general may need to involve an epistemological

shift to include extra-rational ways of knowing (de Quincey, 1994) and

cannot be comprehended by neurochemical brain studies alone. We are in

the midst of a revolution focusing on the study of consciousness (Owens,

1995). Penfield, an eminent contemporary neurophysiologist, found that

the human mind continued to work in spite of the brain’s reduced

activity

under anesthesia. Brain waves were nearly absent while the mind was

just as active as in the waking state. The only difference was in the

content of the conscious experience. Following Penfield’s work,

other researchers have reported awareness in comatose patients (Hunt,

1995) and there is a growing body of evidence which suggests that reduced

cortical arousal while maintaining conscious awareness is possible (Fischer,

1971;West 1980; Delmonte, 1984; Goleman 1988; Jevning, Wallace, &

Beidenbach, 1992; Wallace, 1986; Mavromatis, 1991). These states are variously

referred to as meditative, trance, altered, hypnogogic, hypnotic, and

twilight-learning states (Budzynski, 1986). Broadly defined, the various

forms of altered states rest on the maintenance of conscious awareness

in a physiologically reduced

state of arousal marked by parasympathetic dominance (Mavromatis, 1991).

Recent physiological studies of highly hypnotizable subjects and adept

meditators indicate that maintaining awareness with reduced cortical

arousal is indeed possible in selected individuals as a natural ability

or as an acquired skill (Sabourin, Cutcomb, Crawford, & Pribram, 1993).

More and more scientists are expressing doubts about the neurologists’

brain-mind model because it fails to answer so many questions about

our ordinary experiences, as well as evading our mystical and spiritual

ones.

The scientific evidence supporting the phenomenon of remote viewing

alone is sufficient to show that mind-consciousness is not a local

phenomenon (McMoneagle, 1993).

If

mind-consciousness is not the brain, why then does science relate

states of consciousness and mental functioning to brain-wave frequencies?

And how is it that audio with embedded binaural beats alters brain waves?

The first question can be answered in terms of instrumentation. There

is

no objective way to measure mind or consciousness with an instrument.

Mind-consciousness appears to be a field phenomenon which interfaces

with the body and the neurological structures of the brain (Hunt, 1995).

One cannot measure this field directly with current instrumentation. On

the

other hand, the electrical potentials of brain waves can be measured

and easily quantified. Contemporary science likes things that can be

measured and quantified. The problem here lies in oversimplification of

the

observations. EEG patterns measured on the cortex are the result of

electroneurological activity of the brain. But the brain’s electroneurological

activity is not mind-consciousness. EEG measurements then are only an

indirect means of assessing the mind-consciousness interface with the

neurological structures of the brain. As crude as this may seem, the EEG

has been a reliable way for researchers to estimate states of consciousness

based on the relative proportions of EEG frequencies. Stated another way,

certain EEG patterns have been historically associated with specific

states of consciousness. It is reasonable to assume, given the current

EEG literature, that if a specific EEG pattern emerges it is probably

accompanied by a particular state of consciousness.

As

to the second question raised in the above paragraph, audio with

embedded binaural beats alters the electrochemical environment of

the brain. This allows mind-consciousness to have different experiences.

When the brain is entrained to lower frequencies

and awareness is

maintained, a unique state of consciousness emerges. This state is often

referred to as hypnogogia "mind awake/body asleep."

Slightly higher-frequency entrainment

can lead to hyper suggestive states of consciousness.

Still higher-frequency EEG states are associated with alert and

focused mental activity needed for the optimal performance of

many tasks. Perceived reality changes depending on the state of

consciousness of the perceiver (Tart, 1975). Some states of consciousness

provide limited views of reality, while others provide an expanded

awareness of reality. For the most part, states of consciousness

change in response to the ever-changing internal environment and

surrounding stimulation. For example, states of consciousness are

subject to influences like drugs and circadian and ultradian rhythms

(Rossi, 1986; Shannahoff-Khalsa, 1991; Webb & Dube, 1981).

Specific states of consciousness can also be learned as adaptive

behaviors to demanding circumstances (Green and Green, 1986).ch

Synchronized brain waves

Synchronized

brain waves have long been associated with meditative

and hypnogogic states, and audio with embedded binaural beats has

the ability to induce and improve such states of consciousness. The

reason for this is physiological. Each ear is "hardwired" (so

to speak)

to both hemispheres of the brain (Rosenzweig, 1961). Each hemisphere

has its own olivary nucleus (sound-processing center) which receives

signals from each ear. In keeping with this physiological structure, when

a binaural beat is perceived there are actually two standing waves of

equal amplitude and frequency present, one in each hemisphere. So,

there are two separate standing waves entraining portions of each

hemisphere to the same frequency. The binaural beats appear to

contribute to the hemispheric synchronization evidenced in meditative

and hypnogogic states of consciousness. Brain function is also

enhanced through the increase of cross-collosal communication

between the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

Rhythmic Sound and the Brain

Studies

have shown that vibrations from rhythmic sounds have a

profound effect on brain activity. In shamanic traditions, drums were

used in periodic rhythm to transport the shaman into other realms of reality.

The vibrations from this constant rhythm affected the brain in a very

specific

manner, allowing the shaman to achieve an altered state of mind and

journey out of his or her body .

Brain

pattern studies conducted by researcher Melinda Maxfield into the

(SSC) Shamanic State of Consciousness found that the steady rhythmic

beat of the drum struck four and one half times per second was the key

to transporting a shaman into the deepest part of his shamanic state of

consciousness. It is no coincidence that 4.5 beats, or cycles per second

corresponds to the trance like state of theta brain wave activity. In

direct

correlation, we see similar effects brought on by the constant and rhythmic

drone of Tibetan Buddhist chants, which transport the monks and even other

listeners into realms of blissful meditation.

If your experience with hypnosis is limited or you simply want to accelerate the effectiveness of your hypnosis sessions, and improve your life beyond perceptible measures, just click the link below for your free demonstration with this new state of the art program.

![]()

Interesting Tidbits

A look at the brain of a Somnambulist

|

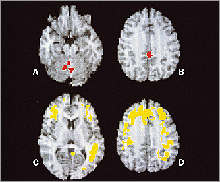

Somnambulism is the act of sleepwalking. Scientists

have studied this interesting phenomenon for generations. Recent studies have shown a burst of delta waves (shown in yellow in the graphic to the right) in the brain of someone who is sleepingwalking. They theorize that the somnambulist triggers a portion of the brain that deals with emotion, and then the body, which is normally at rest, becomes involved. A somnambulist is asleep the entire time he or she is moving about. |

Books

on Brainwave Synchronization |

|

|

Megabrain by Michael Mutchison Scientists have learned more about the brain in the last decade than in all of previous history, and the implications of the latest research are clear: The human brain is far more powerful, and has the potential for immensely greater growth and transformation, than was ever before imagined. These discoveries may constitute the most significant development in learning since the invention of writing. |

|

Awakening

The Mind: A Guide to Mastering the Power of Your Brain Waves by Anna Wise Each moment of our lives, from birth to death, our brains are engaged in an endless symphony of patterns. In Awakening the Mind, Anna Wise reveals how a careful understanding of the four types of brain waves, and the practice of carefully designed meditation exercises that lead to a mastery of each type, can vastly improve everyday focus, memory, concentration, and overall mental awareness. |

|

The

High-Performance Mind: Mastering Brainwaves for Insight, Healing,

and Creativity by Anna Wise Wise discusses and illustrates the four types of brain waves--beta, alpha, theta, and delta--with emphasis on what they do, how they work together, and whether we can use their power. Harnessing human brain waves for heightened creativity, inspiration, and self-healing is the major goal. Several pages of meditation exercises are included with tips on how to relax, all designed to trigger specific brain-wave patterns and achieve a high-performance mind. |

Other Research on Brainwave Synchronization

Adams, H. B. (1965). A case utilizing sensory deprivation procedures. In L. P. Ullman & L. Krasner (Eds.), Case Studies in Behavior Modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Adrian, E. D. & Yamagiwa, K. (1935). "The origin of the Berger Rhythm." Brain, 58, 323-351.

Atwater, F. H. (1988). "The Monroe Institute's Hemisync process: A Theoretical Perspective." Faber, Va: Monroe Institute.

Bandler, R. (1985). "Using Your Brain--For a Change." Moab, UT: Real People Press.

Barber, T. X. (1957). "Experiments in hypnosis." Scientific American, 196, 54-61.

Bremer, F. (1958a). "Physiology of the corpus callosum." Proceedings of the Association of Research on Nervous Disorders, 36, 424-448.

Bermer, F. (1958b). "Cerebral and cerebellar potentials." Physiological Review, 38, 357-388.

Brackopp, G. W. (1984). Review of research on Multi-Modal sensory stimulation with clinical implications and research proposals. Unpublished manuscript--see Hutchison (1986).

Budzynski, T. (1973). "Some applications of biofeedback-produced twilight states." In D. Shapiro, et al (Eds.), Biofeedback and Self-Control: 1972. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

Budzynski, T. H. (1976). "Biofeedback and the twilight states of consciousness." In G. E. Schwartz and D. Shapiro (Eds.), Consciousness and Self-Regulation, Vol. 1, New York: Plenum Press.

Budzynski, T. H. (1977). "Tuning in on the twilight zone." Psychology Today, August.

Budzynski, T. H. (1979). "Brain lateralization and biofeedback." In B. Shapin & T. Coly (Eds.), Brain/Mind and Parapsychology. New York: Parapsychology Foundation.

Budzynski, T. H. (1981). "Brain lateralization and rescripting." Somatics, 3, 1-10.

Budzynski, T. H. (1986). "Clinical applications of non-drug-induced states." In B. Wolman & M. Ullman (Eds.), Handbook of States of Consciousness. New York: Van Nostrand-Reinhold.

Budzynski, T. H. (1990) "Hemispheric asymmetry and REST." In Suefeld, P. Turner, J. W., Jr. & Fine, T. H. (Eds.), Restricted Environmental Stimulation, New York: Springer-Verlag.

Cade, C. M. & Coxhead, N. (1979) "The Awakened Mind: Biofeedback and the Development of Higher States of Consciousness." New York: Delacorte Press.

Cheek, D. (1976). "Short-term hypnotherapy for fragility using exploration of early life attitudes." The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 18, 75-82.

Davidson, R. J., Ekman, P., Saron, C. D., Senulis, J. A., & Friesen, W. V. (1990). "Approach-withdrawal and cerebral asymmetry: Emotional expression and brain physiology." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 330-341.

Deikman, A. (1969). "De-automatization and the mystic experience." In C. T. Tart (Ed.), Altered States of Consciousness. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Deikman, A. (1971). "Bimodal consciousness." Archives of General Psychiatry, 25, 481-489.

Donker, D. N. J., Nijo, L., Storm Van Leeuwen, W. & Wienke, G. (1978). "Interhemispheric relationships of responses to sine wave modulated light in normal subjects and patients." Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 44, 479-489.

Evans, F. J., Gustafson, L. A., O'Connell, D. N., Orne, M. T. & Shor, R. E. (1966). "Response during sleep with intervening waking amnesia." Science, 152, 666-667.

Evans, F. J., Gustafson, L. A., O'Connell, D. N., Orne, M. T. & Shor, R. E. (1970). "Verbally-induced behavioral response during sleep." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1, 1-26.

Evans, C. & Richardson, P. H. (1988) "Improved recovery and reduced postoperative stay after therapeutic suggestions during gneeral anaesthetic." Lancet, 2, 491.

Felipe, A. (1965). "Attitude change during interrupted sleep." Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Yale University.

Foster, D. S. (1990) "EEG and subjective correlates of alpha frequency binaural beats stimulation combined with alpha biofeedback." Ann Arbor, MI: UMI, Order No. 9025506.

Foulkes, D. & Vogel, G. (1964). "Mental activity at sleep-onset." Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 70, 231-243.

Glicksohn, J. (1986). "Photic driving and altered states of consciousness: An exploratory study." Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 6, 167-182.

Green, E. E., Green, A. M. (1971). "On the meaning of the transpersonal: Some metaphysical perspectives." Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 3, 27-46.

Green, E. E., & Green, A. M. (1986). "Biofeedback and States of Consciousness." In B. B. Wolman & M. Ullman (Eds.). Handbook of States of Consciousness. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Harding, G. F. & Dimitrakoudi, M. (1977). "The visual evoked potential in photosensitive epilepsy." In J. E. Desmedt (Ed.), Visual Evoked Potentials in Man: New Developments. Oxford: Clarendon.

Henriques, J. B. & Davidson, R. J. (1990). "Regional brain electrical asymmetries discriminate between previously depressed and healthy control subjects." Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 22-31.

Hoovey, Z. B., Heinemann, U. & Creutzfeldt, O. D. (1972). "Inter-hemispheric 'synchrony' of alpha waves." Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 32, 337-347.

Hutchison, M. (1986). Megabrain. New York: Beech Tree Books. William Morrow.

Hutchison, M. (1990). "Special issue on sound/light." Megabrain Report: Vol 1, No. 2.

Iamblichus. "The epistle of Porphyry to the Egyptian Anebo." In Iamblichus on the Mysteries of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians. Trans. by Taylor, T. London: B. Dobell, and Reeves & Turner, 1895.

Janet, P. (1889). L'Automatisme Psychologique. Paris: Alcan.

Koestler, A. (1981). The Act of Creation. London: Pan Books.

Kooi, K. A. (1971). Fundamentals of Electroencephalography. New York: Harper & Row.

Kubie, L. (1943). "The use of induced hypnagogic reveries in the recovery of repressed amnesic data." Bull. Menninger Clinic, 7, 172-182.

Lankton, S. R., & Lankton, C. H. (1983). The Answer Within: A Clinical Framework of Ericksonian Hypnotherapy. New York: Bruner/Mazel.

Leman, K. & Carlson, R. (1989). Unlocking the Secrets of Your Childhood Memories. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

Lilly, J. C. (1972)). Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer. New York: Julian.

Lubar, J. F. (1989). "Electroencephalographic biofeedback and neurological applications." In J. V. Basmajian (Ed.), Biofeedback: Principles and Practice, New York: Williams & Wilkins.

Mavromatis, A. Hypnagogia: The Unique State of Consciousness Between Wakefulness and Sleep. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987.

Miller, E. E. (1987). Software

for the Mind: How to program Your Mind for Optimum Health and Performance.

Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts.

Moscu, K. I. & Vranceanu, M. (1970). "Quelques resultats concernant l'action differentielle des mots affectogenes et nonaffectogenes pendant le somneil naturel." In M. Bertini (Ed.), Psicofisiologia del Sonno e del Sogno. Milan: Editrice Vita e Pensiero.

Moses, R. A. (1970). Adler's Physiology of the Eye: Clinical Applications. St. Louis: Mosby.

Nemiah, J. C. (1984). The unconscious and psychopathology. In S., & Meichenbaum, D. New York: John WIley & Sons, pp. 49-87.

Oster, G. (1973). "Auditory beats in the brain." Scientific American, 229, 94-102.

Peniston, E. G. & Kulkowski, P. J. (1989). "Alpha-Theta brainwave training and B-endorphin levels in alcoholics." Alcoholism, 13, 271-279.

Richardson, A. & McAndres, F. (1990) "The effects of photic stimulation and private self-consciousness on the complexity of visual imagination imagery." British Journal of Psychology, 81, 381-394.

Rossi, E. L. (1986). The Psychobiology of Mind-Body Healing. New York: W. W. Norton.

Rubin, F. (1968). (Ed.), Current Research in Hypnopaedia. London: MacDonald.

Rubin, F. (1970). "Learning and sleep." Nature, 226, 447.

Schacter, D. L. (1977). "EEG theta waves and psychological phenomena: A review and analysis." Psychology, 5, 47-82.

Schultz, J. & Luthe, W. (1959). Autogenic Training: A Psychophysiological Approach in Psychotherapy. New York: Grune & Stratton.

Sittenfeld, P., Budzynski, T. & Stoyva, J. (1976). "Differential shaping of EEG Theta rhythms." Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 1, 31-45.

Stoyva, J. M. (1973), "Biofeedback techniques and the conditions for hallucinatory activity" In McGulgan, F. J. and Schoonover, R. (Eds), The Psychophysiology of Thinking. New York: Academic Press.

Svyandoshch, A. (1968). "The assimilation and memorization of speech during natural sleep." In F. Rubin (Ed.), Current Research in Hypnopaedia. London: MacDonald.

Swedenborg, E. Rational Psychology. Philadelphia: Swedenborg Scientific Association, 1950.

Tomarken, A. J., Davidson, R. J., & Henriques, J. B. (1990). "Resting frontal brain asymmetry predicts affective responses to films." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 791-801.

Townsend, R. E. (1973). "A device for generation and presentation of modulated light stimuli." Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 34, 97-99.

Tucker, D. M. (1981). "Lateral brain function, emotion, and conceptualization." Psychological Bulletin, 89, 19-46.

Van der Tweel, L. H. & Verduyn Lunel, H. F. E. (1965). "Human visual responses to sinusoidally modulated light." Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurology, 18, 587-598.

Van Dusen, W. (1975). The Presence of Other Worlds. London: Wildwood House.

Walter, V. J. & Walter, W. G. (1949). "The central effects of rhythmic sensory stimulation." Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 1, 57-86.

Wickramasekera, I. E. (1988). Clinical Behavioral Medicine: Some Concepts and Procedures. New York: Plenum Press.

If your experience with hypnosis

is limited or you simply want to accelerate the effectiveness of your

hypnosis sessions, and improve your life beyond perceptible measures,

just click the link below for your free demonstration with this new state

of the art program.